research

Our aim is to understand human visual perception. What is it that allows us to see the world as we do? Research techniques that we use include behavioural psychophysics, computational modelling, eye tracking and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

The lab name derives from our research focus on peripheral

(‘eccentric’) vision. The visual system takes a lot of

interesting shortcuts in the periphery that we think reveal much about visual perception in general. Click the icons below or scroll down to read about some of our current research areas:

visual crowding

One focus of our research is ‘crowding’ - the disruptive effect of clutter on object recognition. In our visual field, objects are typically easy to see when we look directly at them and difficult to see in the periphery (the ‘edges’ of our vision).

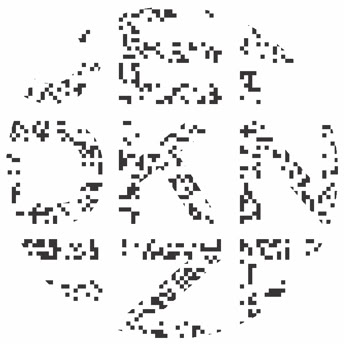

This difference is not simply to do with resolution – even when a target object is large enough to be seen in isolation in peripheral vision, the placement of other objects nearby can make the target appear ‘jumbled’ and difficult to recognise. This is known as ‘visual crowding’. You can see an example below. Fix your gaze on the cross in the centre – the letter ‘E’ should be visible on the left hand side of your peripheral vision. In contrast, you should find it much more difficult to identify the central letter of the three on the right, despite all letters being exactly the same size. This is due to crowding.

It is crowding and not simple resolution that limits our object recognition over more than 95% of the visual field.

Our interest in crowding stems firstly from this fundamental limitation and much of our research is aimed at understanding its underlying basis. We are also interested in crowding because of its elevation in central/foveal vision during development, and in clinical conditions such as amblyopia, nystagmus, and visual-led dementia (see below).

Selected publications:

- Greenwood, JA, & Parsons, MJ (2020). Dissociable effects of visual crowding on the perception of color and motion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(14), 8196-8202. [Download]

- Greenwood, J. A., Szinte, M., Sayim, B., & Cavanagh, P. (2017). Variations in crowding, saccadic precision, and spatial localization reveal the shared topology of spatial vision. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(17), E3573-E3582. [Download]

- Anderson, EJ, Dakin, SC, Schwarzkopf, DS, Rees, G, & Greenwood, JA. (2012). The neural correlates of crowding-induced changes in appearance. Current Biology, 22(13), 1199-1206. [Download]

- Greenwood, JA, Bex, PJ, & Dakin, SC. (2010). Crowding changes appearance. Current Biology, 20(6), 496-501. [Download]

amblyopia

Although crowding does not greatly affect the centre of gaze (where you’re looking) in ‘typical’ vision, it becomes elevated the case of strabismic amblyopia, often known as ‘lazy eye’. Amblyopia is the most common cause of visual impairment in children and affects ~3% of the population. It is defined by impaired resolution in one eye that occurs despite optical correction. In addition, the central vision of the amblyopic eye is also strongly affected by crowding – one of our research areas is to examine whether the mechanisms underlying amblyopic crowding are the same as those that produce crowding in our peripheral vision. We are also interested in the development of new treatment programs for amblyopia, specifically those aimed at the development of binocular vision (unlike traditional ‘patching’ approaches).

Selected publications:

- Kalpadakis-Smith, AV, Tailor, VK, Dahlmann-Noor, AH, & Greenwood, JA (2022). Crowding changes appearance systematically in peripheral, amblyopic, and developing vision. Journal of Vision, 22(6):3, 1-32. [Download]

- Bossi, M., Tailor, V. K., Anderson, E. J., Bex, P. J., Greenwood, J. A., Dahlmann-Noor, A., & Dakin, S. C. (2017). Binocular therapy for childhood amblyopia improves vision without breaking interocular suppression. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 58(7), 3031-3043. [Download]

- Tailor, V, Bossi, M, Greenwood, JA & Dahlmann-Noor, A (2016). Childhood amblyopia: Current management and new trends. British Medical Bulletin, 119(1): 75-86. [Download]

visual development

We are also interested in the development of these visual abilities. Crowding is particularly interesting in this context - where adults can recognise closely spaced objects when gazing directly at them, the same is not true for children. These elevations in foveal crowding are slower to mature than similar processes like visual acuity, placing a significant restriction on the vision of children and on processes such as reading. As with amblyopia, we are investigating whether the same mechanisms could give rise to crowding in these cases.

Selected publications:

• Kalpadakis-Smith, AV, Tailor, VK, Dahlmann-Noor, AH, & Greenwood, JA (2022). Crowding changes appearance systematically in peripheral, amblyopic, and developing vision. Journal of Vision, 22(6):3, 1-32. [Download]

• Greenwood, JA, Tailor, VK, Simmers, AJ, Sloper, JJ, Bex, PJ, & Dakin, SC. (2012). Visual acuity, crowding and stereo-vision are linked in children with and without amblyopia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 53(12), 7655-7665. [Download]

visual-led dementia

Over 50% of people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) experience vision symptoms, with impairments in everyday tasks including reading, driving, and mobility. In Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA), these symptoms are typically the earliest sign of dementia, with memory, language, and executive functions initially spared. These visual symptoms are often overlooked or misinterpreted, leading to gaps in early detection that can delay diagnosis for years. In collaboration with colleagues at the UCL Dementia Research Centre, we have developed the Graded Incomplete Letters Test (GILT) to fill this gap. The GILT measures the recognition of degraded letters, using large, high-contrast letters to assess cortical recognition independently of eyesight/optical factors. Adults with PCA show heavily impaired GILT performance (some struggling to recognise letters with even subtle degradation) whereas typical adults, those with typical AD and visual loss due to common eye conditions like glaucoma can all recognise incomplete letters with high levels of degradation. The test was recently adopted into the UK Biobank with over 30,000 adults having completed the test to date.

Selected publications:

- Yong, KXX, Petzold, A, Foster, P, Young, A, Bell, S, Bai, Y, Leff, AP, Crutch, S, & Greenwood, JA (2024).

The Graded Incomplete Letters Test (GILT): A rapid test to detect cortical visual loss, with UK Biobank implementation.

Behavior Research Methods, 1-13. [Download]

infantile nystagmus

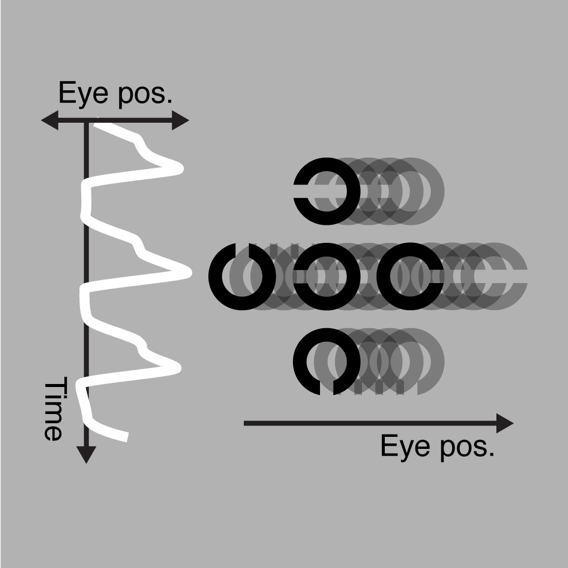

Infantile nystagmus (sometimes referred to as congenital nystagmus) is a visual disorder characterised by involuntary eye movements, with associated deficits in visual acuity. Given reports that elevations in crowding may also arise in these instances, we have been examining the properties of crowding in congenital nystagmus in order to test whether the origin of these effects lies in the same mechanism as crowding in amblyopia and the typical visual periphery (as above).

Selected publications:

- Tailor, VK, Theodorou, M, Dahlmann-Noor, AH, Dekker, TM, & Greenwood, JA (2021). Eye movements elevate crowding in idiopathic infantile nystagmus syndrome. Journal of Vision, 21(13):9, 1-23. [Download]

face perception

A great deal of research suggests that faces are processed in a unique ‘holistic’ fashion within the visual system, distinct from other objects. The classic finding in this regard is that face recognition is disproportionately impaired for upside-down images, unlike the recognition of other objects.

We are currently investigating how this ‘special’ processing arises and how it relates to other visual processes.

One aspect of this continues our research focus on visual crowding (as above) - although some studies have suggested that the crowding of faces may operate in a distinct ‘holistic’ fashion, our findings indicate that the disruption to face recognition in clutter follows the same principles as other visual dimensions (like orientation or colour). We have also examined the orientation selectivity of face recognition - the top face on the right has been filtered so that only the orientations near to horizontal remain, while the face below contains only near-vertical orientations. The clearer identity within the top face suggests that horizontal information carries the greatest amount of information relevant for face recognition. We have recently investigated the way that this sensitivity to orientation differs for upright and inverted faces.

Selected publications:

- Morsi, AY, Goffaux, V, & Greenwood, JA (2024). The resolution of face perception varies systematically across the visual field. PLoS ONE, 19(5), e0303400. [Download]

- Kalpadakis-Smith, AV, Goffaux, V, & Greenwood, JA (2018). Crowding for faces is determined by visual (not holistic) similarity: Evidence from judgements of eye position. Scientific Reports, 8(12556), 1-14. [Download]

- Goffaux, V & Greenwood, JA (2016). The orientation selectivity of face identification. Scientific Reports, 6(34204), 1-13. [Download]

visual hallucinations

Visual hallucinations are false percepts that do not correspond to external stimuli, and can be classed as either simple (e.g., geometric shapes like rings and spirals) or complex (e.g., people or animals). As well as hallucinations induced by psychedelics or neurological conditions, hallucinations can also be induced experimentally by conditions of perceptual deprivation (e.g. Ganzfeld techniques), or by viewing flickering displays (e.g. Ganzflicker techniques). We found that the Ganzflicker produced more simple hallucinations than the Ganzfeld, though both induced complex hallucinations at similar rates. These frequencies were also correlated across individuals, suggesting shared low-level mechanisms likely related to cortical excitability. We have also found that the rate of complex hallucinations induced by these techniques decreases with age.

Selected publications:

- Shenyan, O, Haye, L, Milne, GA, Lisi, M, Greenwood, JA, Skipper, JI, & Dekker, TM (2025). Reduced susceptibility to experimentally-induced complex visual hallucinations with age. Cortex, 191, 188-204. [Download]

• Shenyan, O, Lisi, M, Greenwood, JA, Skipper, JI, & Dekker, TM (2024). Visual hallucinations induced by Ganzflicker and Ganzfeld differ in frequency, complexity, and content. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 2353. [Download]

spatial vision

How is it that we see the shape and location of objects in our visual field? One key aspect of this process is the retinotopic organisation of visual areas in our brain - neurons adjacent to one another on the cortical surface respond to adjacent regions of the visual field. We have recently examined the heritability of these retinotopic maps in early visual areas, following on from earlier work in which we examined individual differences in the perception of object size and the relationship between these idiosyncrasies and the structure of retinotopic maps in visual cortex. We are also interested in the perception of object position and the processes by which we judge the number and density of elements within a given region of space.

Selected publications:

- Alvarez, I, Finlayson, NJ, Ei, S, de Haas, B, Greenwood, JA, & Schwarzkopf, DS (2021). Heritable functional architecture in human visual cortex. NeuroImage, 239, 118286. [Download]

- Moutsiana, C, de Haas, B, Papageorgiou, A, van Dijk, JA, Balraj, A, Greenwood, JA, & Schwarzkopf, DS (2016). Cortical idiosyncrasies predict the perception of object size. Nature Communications, 7, 12110. [Download]

- Tibber, MS, Greenwood, JA, & Dakin, SC. (2012). Number and density discrimination rely on a common metric: Similar psychophysical effects of size, contrast and divided attention. Journal of Vision, 12(6):8, 1-19. [Download]

- Dakin, SC, Tibber, MS, Greenwood, JA, Kingdom, FAA, & Morgan, MJ. (2011). A common visual metric for approximate number and density. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(49), 19552-19557. [Download]

motion perception

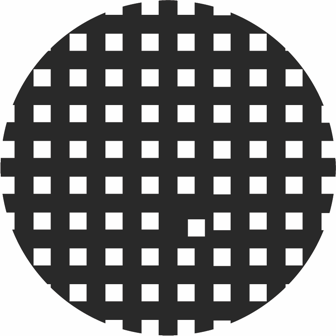

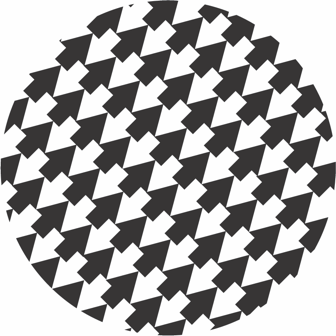

How do we see the direction of a moving object? Our visual system is constantly bombarded with motion - both from objects in the visual field and from our own movement through the environment. Determining the dominant motion signal in a given region is a major problem in these circumstances. One focus of our research has been transparent motion - the perception of multiple overlapping planes of motion in the same place at the same time. This poses a problem for many models of motion perception because it demonstrates that motion perception can be multi-valued at a given point in space - as you can see in the gif on the right. We have investigated the maximum number of motion signals that can be seen simultaneously, in order to provide a constraint on these operations, as well as considering the mechanisms that would allow this to be processed within the visual system.

We are also interested in illusions of motion perception and how these processes interact with spatial vision - for instance, we have investigated the De Valois illusion (where moving objects appear to be positioned ahead of their actual positions in space) and its interaction with the magnitude of visual crowding.

Selected publications:

- Dakin, SC, Greenwood, JA, Carlson, TA & Bex, PJ. (2011). Crowding is tuned for perceived (not physical) location. Journal of Vision, 11(9):2, 1-13. [Download]

- Greenwood, JA & Edwards, M. (2009). The detection of multiple global directions: Capacity limits with spatially segregated and transparent-motion signals. Journal of Vision, 9(1), 1-15. [Download]

- Greenwood, JA & Edwards, M. (2007). An oblique effect for transparent-motion detection caused by variation in global-motion direction-tuning bandwidths. Vision Research, 47(11), 1411-1423. [Download]

- Greenwood, JA & Edwards, M. (2006). Pushing the limits of transparent-motion detection with binocular disparity. Vision Research, 46(16), 2615-2624. [Download]